Description

Only the Few Brave Souls is a song cycle for solo voice and piano, which is inspired by the 100-year anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment, giving women the right to vote. Although the suffragette movement can rightly be criticized, this song cycle seeks to celebrate increased access to the ballot through a musical exploration of the words of three women who fought for that access.

Lyrics

A Royal Blaze of Color

There is a royal blaze of color at the White House gates these nipping winter days. Through the lovely tracery of bare trees, the cold classic lines of the White House have receded into their background.

Instead a gallant display of purple, white and gold banners through the trees holds the eye. They are like trumpet calls.

Many were caught by the lovely sight last week when the suffrage pickets of the congressional union first went on guard at the White House. For the first time in history the President of these United States is being picketed; day after day by the women of this nation is being asked a question that must finally be answered.

We have approached him with delegations. We have approached him with great processions. Women with full and beating hearts. And yet he tells us we must wait, more and more.

Women, it rests with us. Won’t you come and join the standing day after day at the gates of the White House with banners asking, “What will you do Mister President for one half of the people of this nation?”

Come stand there as sentinels, sentinels of liberty, sentinels of self-government. Sentinels, silent sentinels.

-Harriot Stanton Blatch, adapted

from The Suffragist, the weekly organ of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage and the National Woman’s Party, Miss. Alice Paul, Chairman, Vol. IV, No. 55, 17 January 1917, p. 7

The Night of Terror

It was about half past seven when we got to Occoquan Workhouse. I saw men begin to come onto the porch, but I didn’t think anything about it.

Suddenly the door flew open and Whittaker burst in like a tornado. Some men followed him. They were not in uniform.

We demanded to be treated as political prisoners when Mister Whittaker said, “You shut up. I have men here to handle you! Seize her!”

They have taken Missis Lewis in the hall outside. There was a man called Captain Reeves. He was brandishing a stick and shouting, “Damn you, get in here!” The two men handling Dorothy Day were twisting her arms above her head. Then suddenly they lifted her up and banged her down over the arm of an iron bench twice.

They pushed me through a door and I fell against the iron bed. Missis Cosu struck the wall. Missis Lewis doubled over and, handled like a sack of something, was literally thrown in. Her head struck the bed. She didn’t move. We were crying over her when we heard Missis Burns call, “Where is Missis Nolan?” I replied, “I am here.”

At this Mister Whittaker came to our door and told us not to speak or he would put the brace and the bit in our mouth and the straitjacket on our bodies.

-Mary A. Nolan, adapted

from “Jailed for Freedom” by Doris Stevens, copyright 1920. Statement dictated by Mary I. Nolan (72 y.o.) in the presence of Mr. Dudley Field Malone upon release from the Occoquan Workhouse on November 21, 1917.

Only the Few Brave Souls

The founders of this Republic called Heaven and earth to witness that it should be a government of the people, for the people and by the people. And yet the elective franchise is withheld from one-half of the citizens because the word ‘people,’ by an unparalleled exhibition of lexicographical acrobatics has been turned and twisted to mean all who were shrewd and wise enough to have themselves be born boys instead of girls, or who took the trouble to be born white instead of black.

Even if it be true that the majority of women are so ignorant of the full significance of their political disenfranchisement that they are willing to remain in subjection, such ignorance and apathy could not justly be used as an argument against granting full suffrage to the few women who have sufficient intelligence to desire it.

The argument that it is unnatural for women to vote is as old as the hills. Nothing could be more unnatural than that a good woman should shirk her duty to the State.

In all great reforms it is only the few brave souls who have the courage of their convictions and who are willing to fight until victory is wrested from the very jaws of fate.

It is only the few brave souls.

-Mary Church Terrell, adapted

from Terrell’s address “The Justice of Women’s Suffrage,” printed in the Wyandotte Chief, Kansas City, Kansas; February 15, 1900, p. 2.

Program Notes

The cycle opens with “A Royal Blaze of Color,” written in the style of the bright, energetic protest songs that were popular during the suffrage movement. The music changes as the song shifts to a narrative style, providing a proud assessment of the current work of the protesting women, and expressing frustration with the lack of action by the president. Finally, the narrative gives way to a call to advocacy, asking women to ‘come and join the standing.’ The words are adapted from those of Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a writer and a suffragist. After international travels in the late 19th century, Blatch returned to her home country to breathe new life into the women’s suffrage movement, focusing her efforts on recruitment of working-class women. She organized militant street protests and brokered backroom political deals to help advance the cause.

Mary A. Nolan is best known for her telling of the Night of Terror. She was arrested due to her work with the National Woman’s Party which marched in Washington, D.C. to demand suffrage. Because of her advanced age, her sentencing judge urged her to pay a fine, but she chose to go to prison instead. During the Night of Terror (November 15, 1917), guards violently attacked the imprisoned women. Nolan, upon her release, shared the details of her experience, and continued to demonstrate outside the White House as one of the Silent Sentinels. Nolan’s headstone bears her own words: “I am guilty if there is any guilt in a demand for freedom.” Dalton’s setting reflects the intensity of the Night of Terror. Short phrases, often delivered frantically, evoke the confusion, fear, and panic the women must have felt as they were rounded up. The song then melts into a state of near disbelief, as the narrator copes with the violence and cruelty of the ordeal.

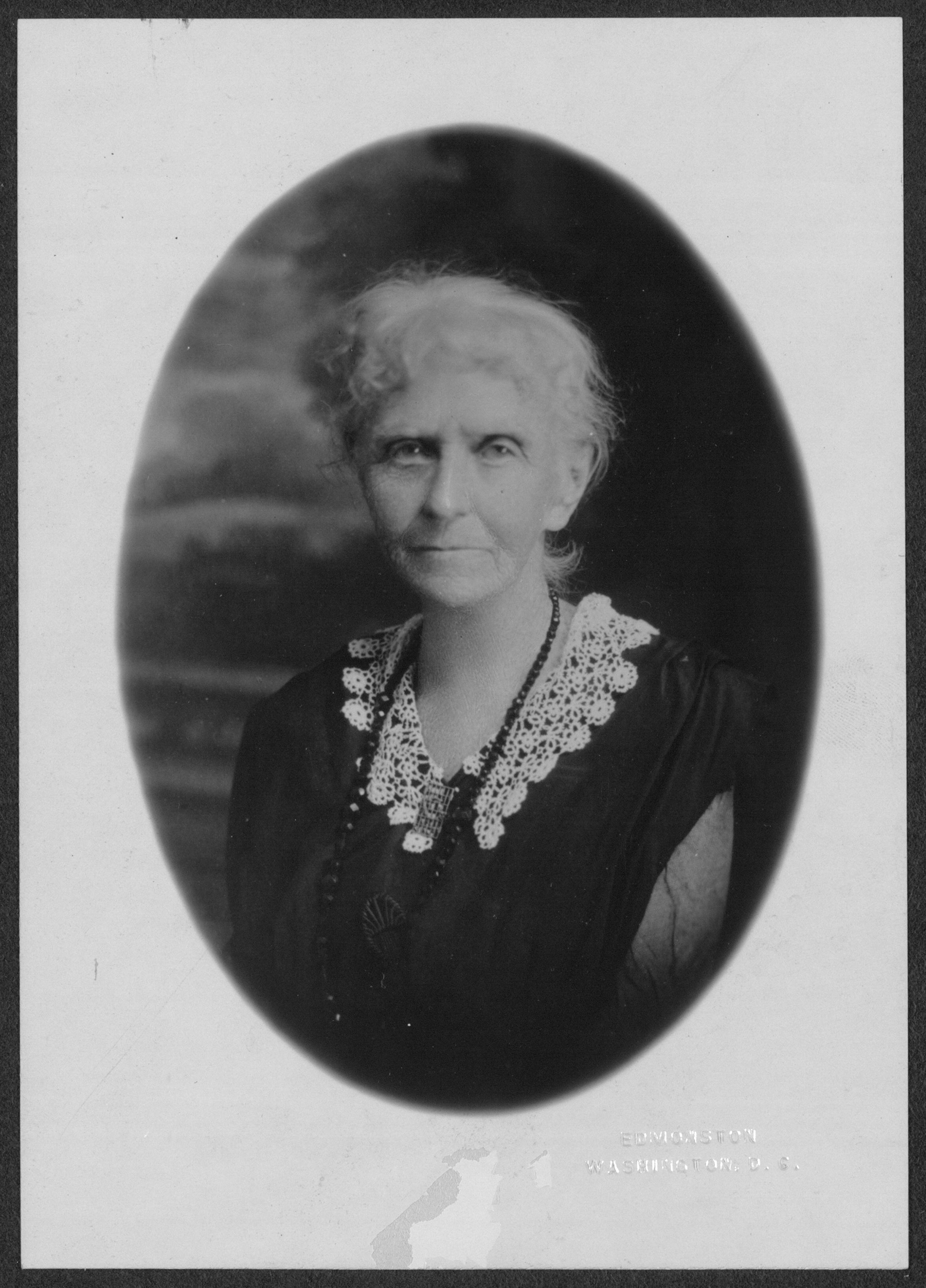

The third and titular movement is adapted from Mary Church Terrell, a champion for both women’s suffrage and racial equality. Born to former slaves, Terrell spent some years teaching before moving to Washington, D.C. When an old friend, Thomas Moss, was lynched in her hometown (Memphis, TN), Terrell became an activist, championing the idea of racial uplift. She fought for women’s suffrage, certain that elevating the status of Black women would elevate the entire Black community. She joined picketers outside the White House and was one of the founding/charter members of the NAACP. She continued her activism throughout her entire life, even protesting segregated public spaces at age 86. Terrell’s words in this movement reflect her frustration that the promises made at the founding of our nation have yet, so many years later, to be applied equally across gender and race.

~ Anna DeGraff

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.